Is it a good idea to put all your eggs in one basket? Here's the case for polymathism versus specialisation.

Exploding The Myth Of Specialisation

Is it a good idea to put all your eggs in one basket? Here's the case for polymathism versus specialisation.

Today, a misconception that specialisation is a necessity for survival prevails as the dominant narrative. It is a narrative based on the questionable premise that we as humans are inherently competitive.

Prior to the modern Western paradigm, other world views (such as the African Ubuntu philosophy – ‘I am because we are’) focused on the co-operative, cohesive side of man, which nineteenth-century Russian evolutionist Peter Kropotkin and more recently genome expert Matt Ridley confirmed is just as deep-rooted a part of human nature as individualistic selfishness might be.

Polymaths were generally less driven by competition than by an inner drive to develop the ‘self’, and that too not necessarily vis-à-vis, or at the expense of another.

The Malthusian idea that population is outgrowing resources, coupled with Herbert Spencer’s Social Darwinism and the notion of the ‘survival of the fittest’ have contributed greatly toward the creation of an ultra-competitive mindset which in turn has manifested in the exploitative culture fostered by colonialism and was subsequently popularised by many large corporations.

In fact, it is the culture of excessive competition that has catalysed the division of labour and propagated the myth of the ‘specialist’, leading to the growth of specialisation. It has created a culture of people protecting ideas rather than connecting them, which of course has led to further specialisation.

So the prevailing assumption – not just today but in many societies throughout history – is that a sustainable income or economic security can only be secured with one specialist occupation at a time.

Professionally, the pursuit of more than one job, field or interest has become synonymous with financial suicide. A negative stigma has been attached to the non-specialist, whose ‘time-wasting activity’ is perceived to come at the expense of his livelihood.

Demeaning the polymath as a financially doomed creature is a practice entrenched in the proverbial linguistics of many of the world’s cultures.

Let’s take common sayings in Eastern Europe, for example: the Poles refer to the budding polymath as someone with ‘seven trades, the eighth one – poverty’, the Estonians ‘nine trades, the tenth one – hunger’, while in Czech Republic they say ‘nine crafts, tenth comes misery’, and in Lithuania that, ‘when you have nine trades, then your tenth one is starvation’.

This can also be found in East Asian cultures: the Koreans say, ‘a man of twelve talents has nothing to eat for dinner’ and the Japanese refer to the polymath as ‘skilful but poor’.

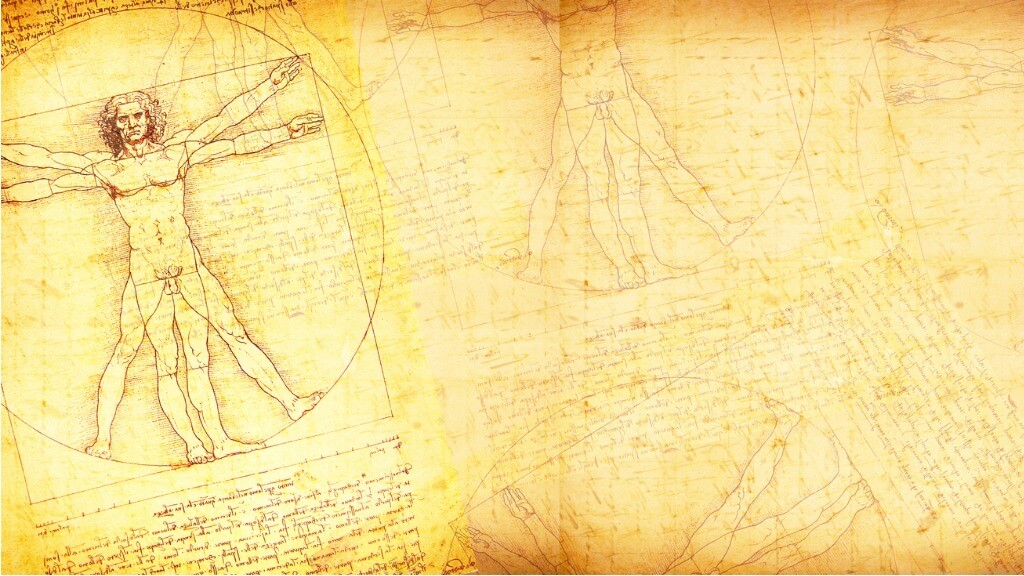

Even societies that produced some of the greatest polymaths think the same: the Greeks say, ‘he who knows a lot of crafts lives in an empty house’ and the Italians, the descendants of da Vinci, Michelangelo, Alberti and Bernini, have come to see this breed as being ‘expert of everything, master of none’.

While the above idioms are translated from their native languages, in which the meaning is most likely more nuanced, the underlying idea is the same as the ‘jack of all trades, master of none’ and is indicative of the ongoing cynicism surrounding the polymath’s ability to survive, accumulate and provide.

This notion needs serious revision. Occupational diversification, which is a common mark of the polymath, is actually often the surest means to survival. During a tough economic climate, people feel extremely vulnerable if their particular field is shrinking in its need for a workforce.

As Yuval Noah Harari concludes in his recent book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, adaptability to inevitable career changes will be an essential survival strategy for the coming decades.

So a more diverse range of skills means that the individual is confident of their capacity to obtain employment in a range of fields. This can give the individual a greater sense of empowerment which ultimately leads to greater productivity and efficiency.

Education ought therefore to be focused on developing skills that can be applied to more than one domain or at the very least be transferable, particularly as what one might specialise in today could be out of date tomorrow, given the economically, politically and technologically volatile times in which we presently find ourselves.

Just as countries (economies) are realising that specialisation in one economic sector is unwise and diversification is the best policy, individuals ought to understand this, too. Moreover an individual’s polymathy can have a substantial economic benefit for society at large.

Princeton economist Ed Glaeser studied specialisation and diversity in urban city labour markets and concluded that it is greater diversity (rather than specialisation) of labour that leads to economic growth, simply because there can be more skills and knowledge spillover between industries.

This is important because having a diverse set of skills mean that the labour market can appropriately respond to market demands according to the changing needs of the economy, especially if education is to continue to be hooked up to economic success.

Moreover, the ‘job for life’ model is becoming extinct. The threat of redundancy is increasing and chances of promotion decreasing. Work in business or the arts rarely provides a sure income. Careers (and therefore financial security) in sports and military are especially short-lived.

And those professions traditionally considered stable are no longer so. After twenty five years of experience as a careers adviser, Katherine Brooks concludes that one specialist occupation is simply not sufficient for one’s economic security.

Multiple careers, she suggests, are not a luxury but a necessity, especially in current times. ‘The chaos of today’s job market means job seekers must be flexible and adopt their talents to a variety of settings.

In this economy, you really can’t focus on just one career plan. You need to consider plans B, C and maybe even D, simultaneously. You need to consider a variety of Possible Lives’. It is wise, it seems, to place eggs in many baskets. Specialise at your peril.

This is an edited extract from The Polymath: Unlocking the Power of Human Versatility by Waqās Ahmed (Wiley, January 2019).

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!