The label 'disruptive business' is something of a buzzword, and not as potent a descriptor as it used to be.

The Two Types Of Disruptive Business

The label 'disruptive business' is something of a buzzword, and not as potent a descriptor as it used to be.

Virtually every business working in and around technology (and many outside) claims to be “disruptive” in some manner, with the phrase now becoming a requirement rather than a useful way to differentiate a business’ value and trajectory.

However, it’d be wrong to cave to cynicism and to jettison the use of the word “disruptive” entirely: startups and tech companies so often describe themselves as disrupting the market because most of them are disrupting the market. Rather, we should instead respond to claims about a business’ disruptiveness by asking how it aims to disrupt its market.

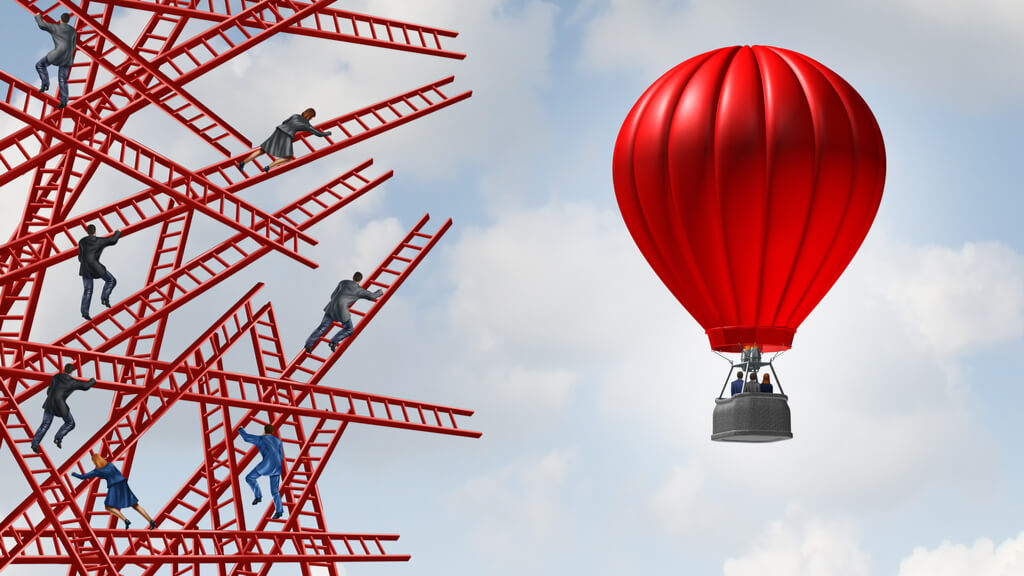

This question is very useful, because it reveals an important distinction between types of disruptive businesses. Roughly, we can break down all ‘disruptive’ businesses into either of the two categories below:

- Category-defining businesses – these are one of the first businesses of their type on the market, and become the template for whole new sectors

- Category-refining businesses – these challenge incumbents in an existing sector by delivering the same product or service, but executing it much better

For the sake of brevity, I’ll refer to a business in the first category as a definer and a business in the second category as a refiner. What do these terms mean in practice?

Type 1: The Definer

The modern search engine didn’t really exist before Google pioneered a new algorithm called PageRank, which ranked search results according to the number and quality of page-links across the web.

This was a total step-change compared to earlier engines, which were slower and produced less useful results. As a result, Google succeeded in creating a platform and model that everyone else wanted to emulate.

Google is a perfect example of a definer, and it is joined in this regard by many other leading big tech companies. For example, Amazon defined the business model, logistics and technology behind online retail and cloud computing services, and Apple defined the modern smartphone market through the development of the iPhone.

Before the innovations from these companies, none of their respective markets existed. Their success lies in being the ones to create that market and leverage their expertise to scale up and assume a position of continued market leadership.

Type 2: The Refiner

SpaceX has reshaped the space transportation industry. It has slashed the cost of getting material into space down from $18,500/kg in 2000 to around $2,700/kg today, which in turn has put vast amounts of new endeavours on the table, all the way from high-bandwidth satellite constellations that can provide the world with free internet to the first person on Mars.

This makes SpaceX an ideal example of a refiner. The space transportation industry has existed for decades, with the underlying technology behind rockets and a business model centred around taking out launch contracts not having changed since the 1970s.

However, by the early 2000s, the industry had become ossified owing to the incumbent cartel of defence and aerospace contractors having no good reason to innovate and drive costs down and push quality upwards - they had no viable competition, so there was no incentive to put in the legwork.

What SpaceX did was challenge the cartel through developing new technologies that would cut down the cost of getting material into orbit. Chief among SpaceX’s new tech was developing a way to save and reuse rocket boosters, which had historically been destroyed after one use.

Through pushing this cost-saving innovation into the space transportation market, SpaceX has turned the industry on its head and forced the old cartel players to imitate it in order to compete.

What’s equally true for space is true for other industries, and the role of the refiner remains the same: to disrupt their industry through prying away customers with a cheaper and/or better solution than the market’s incumbents.

This category is where my own business, Wasabi, would fall, as we offer a cloud storage alternative to Amazon that’s one fifth of the cost.

What does this difference mean?

As the two examples above hint at, the distinction between definers and refiners profoundly influences the business strategy of a company as it seeks to disrupt the market in some way.

A defining business’ main issue is in successfully finding a niche where it can carve and define a market. Amazon succeeded because they provided something new to the market, and bested other early e-commerce and cloud computing businesses through nailing their product to meet the needs of the consumer.

The main challenge facing a definer, then, is to make sure their product or service addresses a hitherto neglected need in the first place.

A refining business’ main issue is successfully challenging the market incumbents and finding a way to pry customers away from existing actors. SpaceX succeeded because it managed to provide space transport services of comparable quality to the incumbents, while being extremely cheap.

This affordability came from it developing new technology that cut costs dramatically, which in turn required a decade-long programme of intensive R&D and testing to prove their viability.

The main challenge facing a refiner, then, is to have enough capital to develop an attractive alternative to incumbents and to win the confidence of the market.

For founders and investors the definer/refiner distinction shouldn’t be treated as an academic difference. Rather, this distinction should be seen as casting light on one of the central qualities of a business with profound ramifications as to what a viable medium-to-long run business strategy looks like.

David Friend is co-founder and CEO Wasabi.

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!