Chairman and founder of cognitive health company MyCognition

View Author ProfileKeiron Sparrowhawk, founder of cognitive health company MyCognition, reveals the research behind the neuro-boosting apps and explains how they could help older entrepreneurs.

Opinions

Brain Training Apps: Are They Any Good For Entrepreneurs?

Keiron Sparrowhawk, founder of cognitive health company MyCognition, reveals the research behind the neuro-boosting apps and explains how they could help older entrepreneurs.

Brain training games - apps designed to exercise your mind and help you to fulfil your mental potential - are a craze. The number of people who have downloaded brain training apps from just a few of the leading US firms is fast approaching 100 million, but like many crazes, they have stimulated controversy.

Sceptics have argued that brain training is ineffective and that computerised cognitive training only improves in-game performance with no genuine real-life benefits. However, this frequent critique is being answered by an increasing number of prestigious trials demonstrating both immediate and lasting gains from brain training.

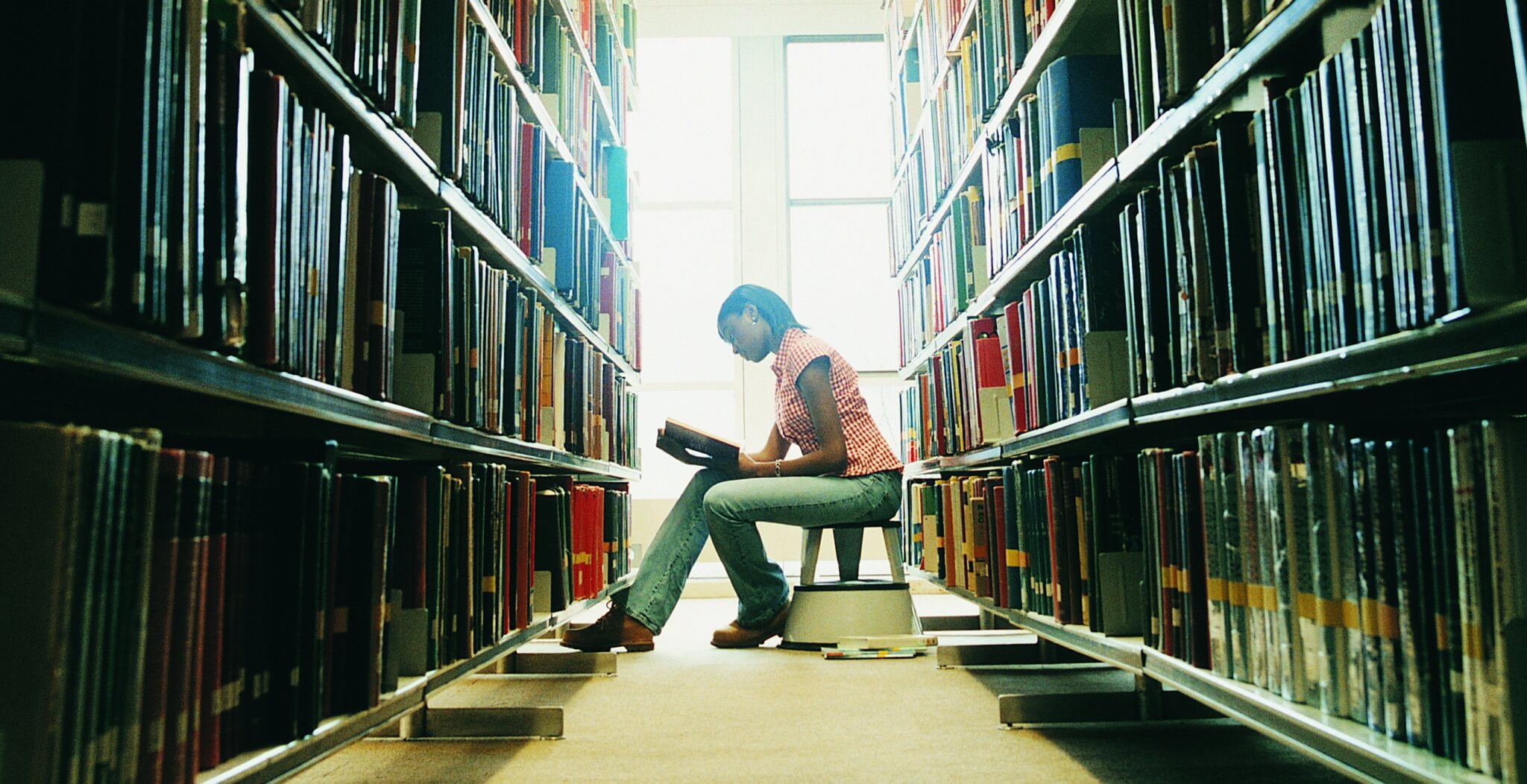

Brain training is proving to have a very broad appeal and is catering to all age groups, from the newly retired seeking to stave off dementia, through to young professionals trying to give themselves an edge in the workplace and further to children of all ages and abilities attempting to get a better grade or trying to overcome a special educational need.

Over the last few years, tens of millions of people of all ages have downloaded and regularly played such games, forming a market that will grow from $210m in 2005 to an estimated $6bn by 2020. What is the idea driving this meteoric rise?

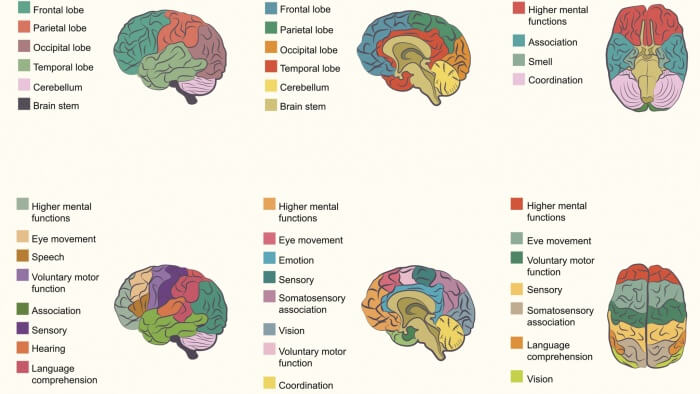

The science behind brain training

The concept of brain training is based on the theory of neuroplasticity – the idea that the brain, far from being a static organ, is constantly changing, renewing, re-growing – just like any other bodily organ.

Its evolution is based on patterns of mental activity: the aim of brain training is to concentrate effort in key areas to direct the flow of growth of neurones and neuronal connections, building new pathways that enable us to adopt new and better habits. Just as we can develop and improve our bodies through physical exercise, we can also develop and improve our mental wellness by exercising our minds.

Monitoring individuals playing certain video games reveals that the stimulus causes new zones to fire up in the brain. This means that new neural pathways are being created, as shown by the increased blood flow to these areas. The new and enlarged blood vessels carry greater quantities of nutrients and oxygen to these typically less active areas of the brain and clear away the toxins, allowing for accelerated growth of brain tissues.

Just as smoking, poor nutrition, high blood pressure and cholesterol can lead to poor cognition by clogging up arteries and obstructing blood flow to the brain, brain training is designed to have the reverse effect, driving blood flow and therefore nutrients to specific areas of the brain, helping to shape its growth.

Research has shown that for this to occur, brain training needs to be done regularly and over a sustained period of time. Repetition of tasks is a way to ensure growth and the laying down of good habits.

Clearly however, there is a wide variety of games and products out there, from casual online memory games and crossword apps through to scientifically developed and rigorously tested cognitive evaluation assessments and programmes such as MyCognition’s.

It’s an incredibly broad landscape and unsurprisingly some products are markedly better than others. While generalisations are partly necessary for this debate it is important to remember that each product should be assessed on its individual merits.

So… does brain training actually work?

The debate over the merits of brain training is an issue that still divides the scientific community. In late 2014, 69 neuroscientists from around the world signed an open letter arguing that there wasn’t sufficient proof behind the concept of brain training. At the heart of their objection is the idea that programmes don’t improve your overall intelligence or even cognition: they simply make you better at the game itself.

It is an objection that has found support in tests such as a 2014 trial by the University of Sydney, according to which brain training had no demonstrable effect on executive function (strategic planning) and attention.

The debate has recently shifted however, as these objections have been countered by a March 2015 study in The Lancet, in the first true randomised controlled trial featuring brain training. The study, based in Finland took 1,260 people at risk of dementia, aged from 60 to 77, and randomly allocated them to an intervention or a control group.

Over two years the groups were monitored and the intervention group was given health advice, and followed physical exercise and intensive brain training sessions.

When assessed at the end of the trial using a standard neuropsychological test battery (NTB), the group’s overall scores were 25% higher than the control group. Taking into account the benefits gained from the health advice and exercise, this impressive result strongly suggests that brain training can play a central role in preventing cognitive decline and improving mental faculties.

What clearly emerges from the scientific debate is the need for reliable metrics for cognition and for properly conducted clinical trials. We all get better at games as we play them, so we need an independent test of cognition itself.

This is what MyCognition has sought to create with MyCQ, a digital group of psychometric tests developed in partnership with Cambridge University, which gives a quantitative score for core areas of cognition, such as working memory and psychomotor speed. The MyCQ assessment also enables people to measure their cognitive improvement over time.

Perhaps the strongest evidence in favour of brain training relies on this kind of independent test. A 2014 trial published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience divided over 900 students into a brain training group and a control group, assessing them before and after brain training with a standard reasoning test in which individuals had to summarise texts, relying on recall, inference skills, speed and executive function (the ability to plan ahead strategically).

In the post-training assessment the trained group’s performance was markedly higher while the control group’s results hardly changed at all. Interestingly, the greatest improvement was for the pupils considered to be socially deprived in the training group, whose ‘gist reasoning’ scores were as much as 25% higher.

This tells us that brain training might be an area where we have a chance at levelling traditional social disadvantages, something we have struggled to do so far. This evidence suggests that if the training is applied and monitored properly, that brain training does actually work.

Can brain training offer lasting benefits?

The brain works in patterns, relying on thousands of habits which we follow without conscious thought. Brain training embeds new habits in the mind, such as better ways of paying attention to new information (e.g. when reading a report, or listening in class), which in turn promotes memory and recall.

These positive mental habits then become established and support the completion of a myriad of other tasks, from shopping to holding meetings at work. The repeated use of these processes, in normal daily life, even once the actual training is over, helps to secure lasting cognitive gains.

A recent study1 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society tracked 2,800 individuals over time, brain training some while monitoring others as a control group. The study found significant differences even 10 years later between the reasoning-trained group and the lower-performing control group.

Nearly three-quarters (73.6%) of reasoning-trained participants were still performing reasoning tasks above their pre-trial baseline, against 61.7% for the control group. The contrast is even starker for speed: 70.7% of speed-trained participants were performing above baseline levels compared to less than 50% of controls.

Therefore, in well-conducted studies, we see lasting benefits.

Where is the debate headed in future?

At this point, the voices of sceptics have been matched by encouraging findings from well-respected sources…and so the debate goes on. The next step in research is to explore further the impact brain training has on each of the five cognitive domains.

The 2015 Lancet study, for instance, found that scores in executive functioning were 83% higher in the brain training group, and 150% higher for processing speed. These are vast gaps relative to the other domains and an intriguing avenue for future research.

What is indisputable is that brain training is only going to become increasingly popular as more people become aware of its potential benefits. By combining technological innovation with the highest standard of academic research I am confident that we will realise the true and exciting potential of brain training.

As we look to combat the ever growing challenges of stress, anxiety and depression in our society, together with cognitive degenerative diseases associated with an ageing population, brain training could represent a very powerful tool. It’s going to be a very exciting journey of discovery for all of us concerned.

1 Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study, carried out by the BrainHealth Center of the University of Texas in Dallas, published in 2014.

Most read in Opinions

Trending articles on Opinions

Top articles on Minutehack

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!