Stopping Formula One In its Tracks: British Motorsport After Brexit

Will Brexit ruin the supply chain that underpins British motor sport?

Formula One (F1) is widely regarded as the pinnacle of world motorsport. The industry is worth around $4 billion a year, and between them the ten F1 teams spend $2.6 billion every year on technology, research and development in the pursuit of glory.

With seven of the ten F1 teams based in “Motorsport Valley” (an area covering the Midlands and Oxfordshire), the sport is well and truly embedded in the heart of Britain. These teams, many of which are foreign-owned, have made a considered decision to call Britain home.

However, with the country’s exit from the European Union fast approaching, is this niche industry under threat? Or does Britain risk losing its position as the jewel in the F1 crown to other countries?

Currently, the automotive sector as a whole has a shortage of around 20,000 professionals. It is an industry in transition, and one which is facing significant difficulties.

Against a backdrop of falling domestic car sales from leading manufacturers such as Jaguar Land Rover, Honda set to close its Swindon car plant in 2021, and Nissan’s recent decision not to build its next generation X-Trail model at its flagship factory in Sunderland, further difficulties are undoubtedly on the horizon.

But for F1, the concern is how these wider issues could replicate themselves in the motorsport industry, which is already fiercely competitive due to changing regulations. In the case of a no-deal Brexit, there are several aspects of the industry’s operations which are expected to be severely disrupted.

Logistics are a key issue. Jonathan Neale, the chief operating officer at McLaren, recently explained that “McLaren F1 takes 40 tons and 100 people and we pop up at an event every two weeks around the globe in 20 countries and five continents, through a variety of customs borders, to put the show on the road. Currently, there are well-trodden paths in how we manage customs and borders in order to move seamlessly.”

These “well-trodden paths” and seamless transitions between customs and borders could become considerably more complicated after Brexit, with extra administrative burdens and costs placed on teams as they travel across the globe to compete in races.

Each team has a workforce made up of numerous nationalities, and Neale suggests there is a real risk to their ability to “deliver the show” if restrictive measures at borders cause delays.

The Spanish Grand Prix in Barcelona is the first European race of the F1 season, and will take place around six weeks after the UK is due to leave the European Union. If these barriers do manifest in the way that many are anticipating, they will be highly visible.

Stricter border controls won’t just affect motorsport’s logistical operations. As a highly international sport, talent acquisition and retention are now central to the industry’s concerns about the impact of Brexit. McLaren’s team employs over 800 people and has 23 different nationalities in its engineering group alone.

Maintaining a diverse workforce made up of the most talented people – irrespective of nationality or other factors – is of paramount importance to McLaren, and Neale is alive to the real risk of “getting into crazy, administratively costly and time-consuming visa requirements either for retention or for future recruitment”.

Understandably, F1 teams want to be able to hire the best people for the job without worrying whether their nationality will pose an administrative visa burden.

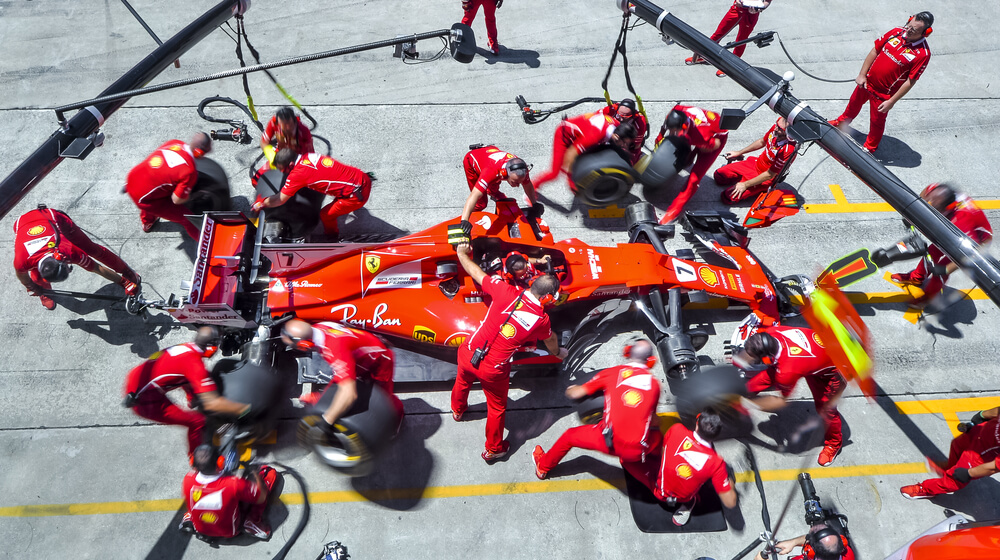

In addition to concerns about motorsport logistics and workforce supply, disruption to the supply chain is a potential threat which would have significant consequences for the industry. An F1 car has about 14,000 parts, the majority of which are sourced from numerous small-to-medium size enterprises in the UK and across Europe.

Indeed, some complex assemblies will cross many borders before they arrive in the UK. Neale explains that “if every time a border is crossed there is a transaction, it introduces a huge amount of inertia and inefficiency to our supply chain”.

With inefficiency comes extra cost; McLaren argue this money ought to be invested in the sport, not spent dealing with administrative and logistical roadblocks.

Unsurprisingly, it is not just McLaren who are wary of the threat Brexit poses to F1. Similar concerns resonate across all the teams based in Britain. Toto Wolff, CEO of Mercedes’ F1 team, describes Brexit as “the mother of all messes” and has made it clear that he believes a no-deal Brexit would “have a major impact in terms of our operation going to the races and getting our car developed”.

Indeed, Wolff has stated that he believes the three teams based elsewhere (Ferrari, Toro Rosso and Alfa Romeo) would have a huge advantage over the UK-based teams.

With 29 March 2019 fast approaching and a no-deal Brexit looking like a distinct possibility, F1 teams (and the automotive industry generally) must be alive to the obstacles that could be on the horizon. The risk of UK-based F1 teams relocating after Brexit, especially if the country leaves without a deal, is genuine.

This would have serious ramifications not only for the sport but for the British-focused supply chain that underpins it. While a smooth exit from the European Union could mean that Britain remains the heartbeat of F1, the uncertainties of a no-deal Brexit look set to put the brakes on the sport as we know it.

Phil Hutchinson is senior associate at law firm Mills & Reeve.

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!