Tax Hikes In Store In Wednesday’s Budget – If Sunak Follows Lesson Of History

Post-election Budgets tend to contain big tax rises, figures show.

Rishi Sunak could be tempted to announce a hefty package of tax rises in his Budget speech on Wednesday – if history is anything to go by.

The first Budget immediately after a general election has traditionally been used by a Chancellor to introduce a host of tax increases.

The Budgets that followed the 1992, 1997, 2001, 2005, 2010 and 2015 elections all saw a jump in the amount of tax levied by the government – some of them ranking among the biggest tax-raising Budgets of the past 50 years.

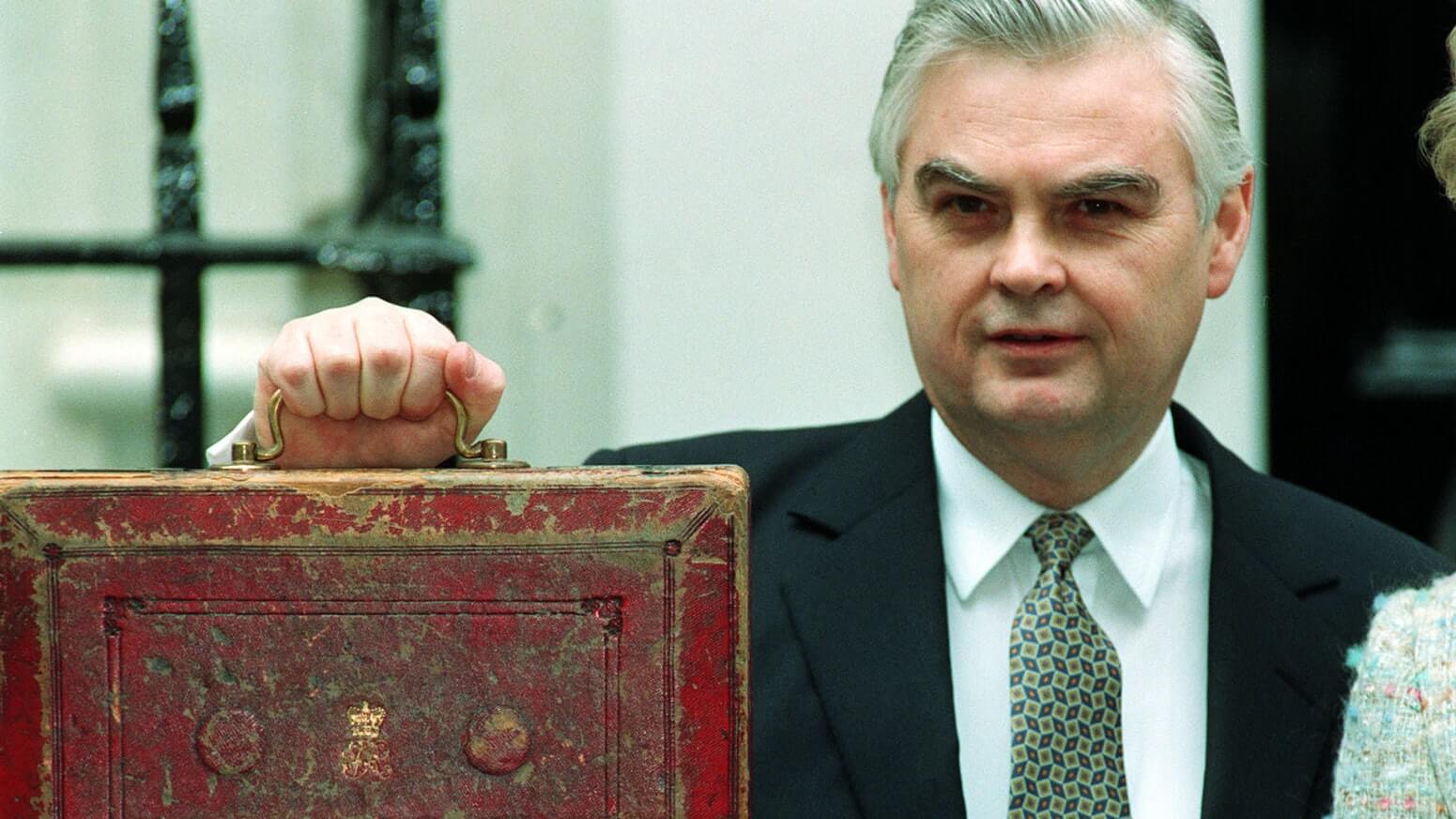

Topping the list is the Budget of March 1993. Coming 11 months after the 1992 election, it saw then-chancellor Norman Lamont unveil tax rises adding up to a massive £26.3 billion (when converted into 2019-20 prices).

Five of the top 10 tax-raising Budgets since 1970 have all followed general elections, according to the PA news agency’s analysis of figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility.

As well as Mr Lamont’s Budget, they also include Gordon Brown’s Budgets of April 2002 (which increased taxes by £17.0 billion) and July 1997 (£11.2 billion), George Osborne’s Budget of June 2010 (£10.2 billion), and Denis Healey’s Budget of March 1974 (£18.5 billion).

Only one post-election Budget in recent years has bucked the trend for tax rises: Philip Hammond’s Budget of November 2017, which saw a £2.4 billion net decrease in new tax measures.

The Budget immediately after an election victory is arguably the ideal time to put up taxes.

A chancellor knows they are at the furthest point away from the next election, and also in most need of new sources of income to fund manifesto promises.

The temptation is therefore great to get “bad news” out of the way sooner rather than later.

Mr Sunak might conclude that Wednesday’s Budget is just such an occasion, given that the next general election is not scheduled to take place until May 2024.

By contrast, big tax-cutting Budgets tend to occur later in the life of a government – often just before a general election.

This was true of Mr Healey’s Budget of April 1978, the last of Jim Callaghan’s Labour government, which saw a sizeable net decrease in tax measures totalling £22.3 billion.

Mr Brown went for the same strategy in March 2001 (a decrease of £5.5 billion), as did Mr Osborne in March 2015 (down £0.6 billion), though the pattern for pre-election tax cuts is not as consistent as that for post-election tax rises.

For example, Ken Clarke’s Budget of November 1996 – the last to take place during John Major’s Tory government – was a modest affair that overall delivered a comparatively small tax rise of £0.9 billion.

It was a very different story in Mr Clarke’s first Budget three years earlier, which saw him unveil tax rises totalling £14.3 billion.

History shows that chancellors cannot be easily pigeonholed as purely tax-risers or tax-cutters.

Rather they tend to try to shape their Budgets according to how close – and how far away – they are to having to face voters at the ballot box.

If Mr Sunak’s first Budget does turn out to include a raft of tax rises, he will only be following in the footsteps of chancellors Tory and Labour alike, stretching all the way back to Mr Healey in the 1970s.

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!