Former BoE chief economist Andy Haldane says Britain is in an era of volatile inflation, low expansion.

Shortages, Inflation And Slow Growth Fog UK Economy

Former BoE chief economist Andy Haldane says Britain is in an era of volatile inflation, low expansion.

Britain's economic bounce-back after coronavirus lockdowns is being hampered by problems in supply chains, a jump in inflation and the risk of a rise in unemployment, complicating the task for policymakers of steering the recovery.

Former Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane says Britain is in an era of volatile inflation, low expansion.

Financial markets now think the BoE is all but certain to raise interest rates by February but some economists, worried by signs of a flagging recovery, aren't so sure.

Below are some of the gauges of Britain's economy that are likely to be on the minds of economic policymakers.

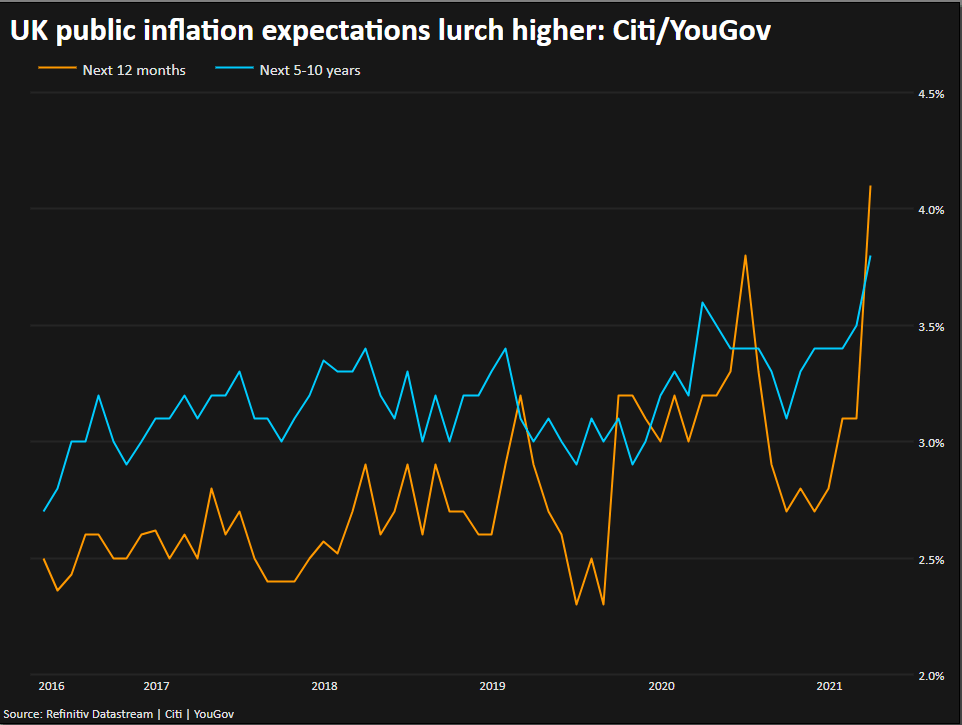

INFLATION

Britain's inflation rate hit 3.2% in August, its highest in almost a decade. Some one-off factors accounted for the record jump from July but the BoE thinks inflation is heading above 4%, more than double its 2% target.

The BoE is watching for any signs that consumers are losing confidence that inflation will be contained in the longer run.

Public expectations for inflation in the year ahead rose sharply in September, according to a Citi/YouGov survey which may have weighed on the minds of BoE rate-setters. They said last month that the case for raising rates was strengthening.

UK public inflation expectations lurch higher

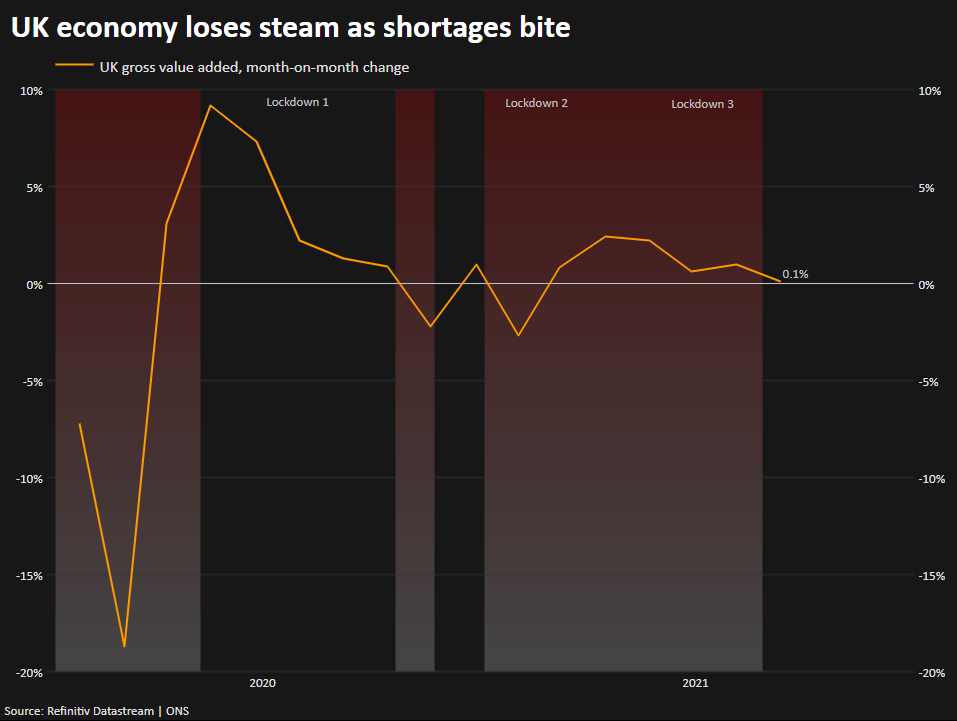

GROWTH FADING?

While Britain's economy grew rapidly earlier this year as it reopened from a third COVID-19 lockdown, the latest readings show this momentum has largely dissipated. Economic growth slowed to a crawl in July, according to official data, and surveys of businesses and consumers suggest sluggish growth persisted into the second half of the year - even before the most severe supply chain problems seen in recent weeks.

UK economy loses steam as shortages bite

SUPPLY CHAIN PROBLEMS

There has been no let-up in the supply chain and staffing problems for British manufacturers dealing with hefty delays from suppliers, according to the latest IHS Markit/CIPS survey of businesses.

That was even before panic-buying at petrol stations, caused by a shortage of tanker drivers, led in late September to the biggest week-on-week drop in car traffic since early June - another unpromising sign for the economy.

The shortage of workers, something seen in other economies around the world, has worsened since Britain decided to leave the European Union and end free movement of workers from the bloc. But Prime Minister Boris Johnson denied on Tuesday Britain was in crisis and said its "natural ability to sort out its logistics and supply chains is very strong."

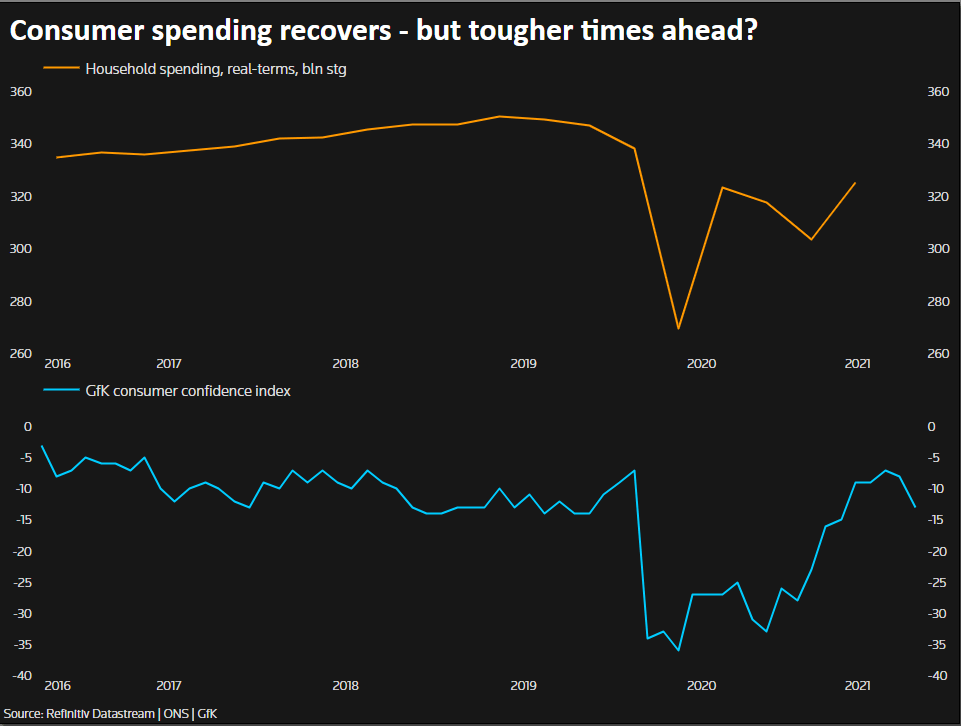

CONSUMER SPENDING

The supply chain disruption and rising inflation prompted a hefty hit last month to the GfK gauge of consumer confidence - historically a good indicator of household spending.

Households are also facing cuts to state benefits and tax increases for working people.

BoE data published last week suggested consumers are once again leaning more towards saving than spending.

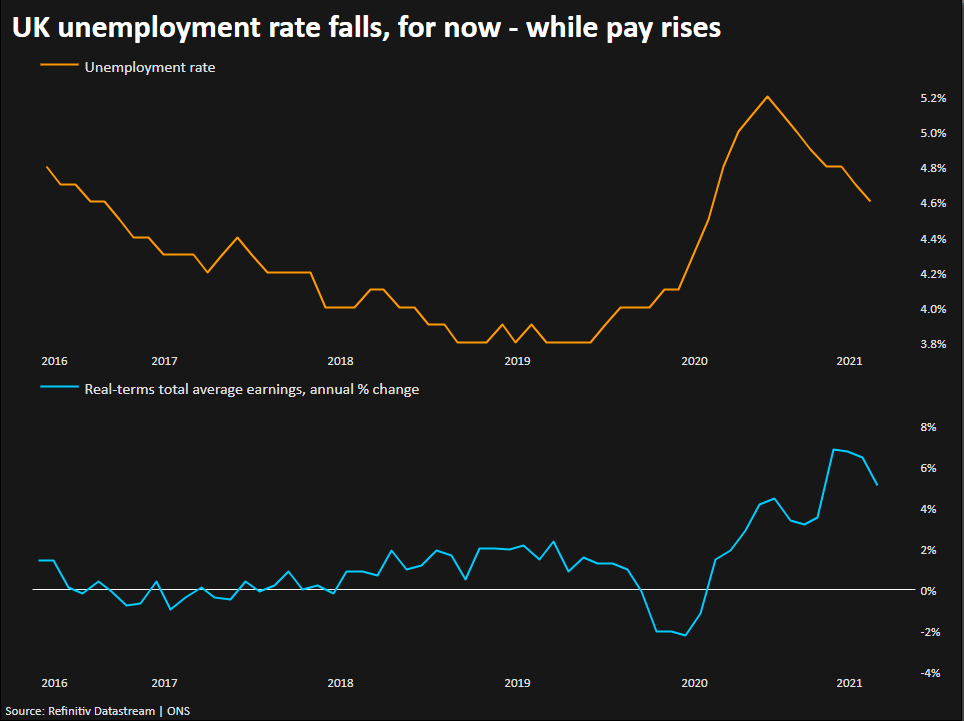

JOBS AND WAGES

Britain's unemployment rate has fallen in six of the last seven monthly reports, helped by the economic recovery and the government's jobs-protecting furlough programme.

That scheme ended at the end of September and the BoE is keeping an eye on whether unemployment is about to rise again.

Wages have been rising fast although the official measure of earnings growth has been boosted by statistical distortions caused by the pandemic. Still, inflation has started to bite into earnings: the official real-terms measure of total wage growth has declined for three months running.

(Reporting by Andy Bruce, Editing by Timothy Heritage)

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!