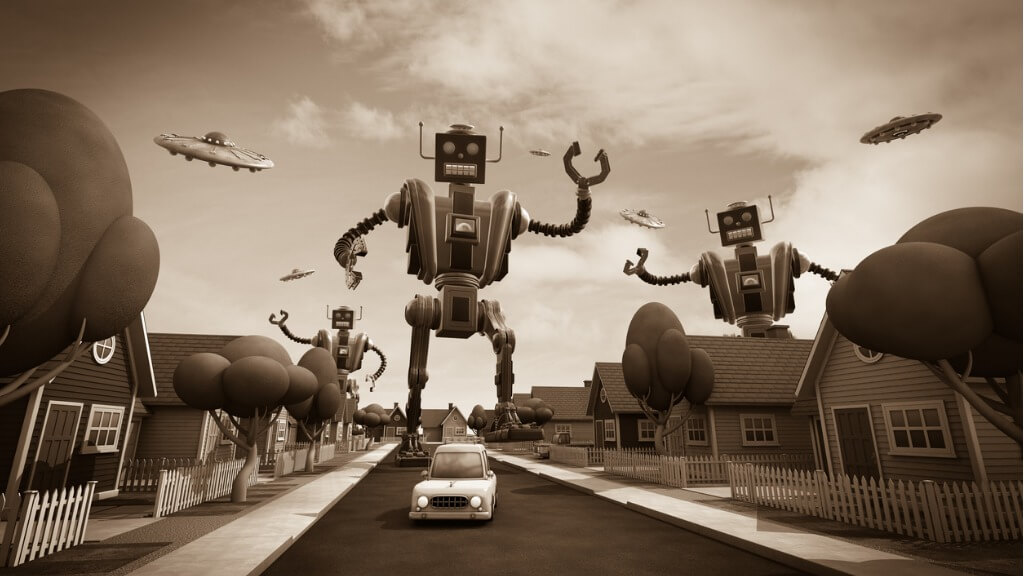

The Robots Are Ready, But Is The Economy?

Automation is upon us, but is the world prepared for it's economic and societal side-effects?

It’s hard to imagine anything other than the dystopia of a fully-automated robot workforce, given the amount of column inches and air time dedicated to the topic.

Technological advances over the past decade have seen huge changes, at breakneck speed, to the way we do business and there’s no sign of that innovation slowing down. But just how concerned should we be about the supposedly imminent takeover of a robot workforce?

The reality is that some industries are more immune than others. Companies such as Uber are making no secret of their plans to one day automate their service, stripping thousands of drivers of jobs. Whereas the area my business operates in - professional services - is, for now, still somewhat dependent on the ‘human touch’.

Looking to history for context, we have seen sweeping transformations in the labour market before. The difference between the industrial revolution and today’s technological revolution is that the former took place over 100 years, whereas the latter has taken little more than two decades to entirely transform the way we work, communicate and interact.

We can trace inflated anxiety about automation back as early as the 1960s. Since the early days of electronic data processing, administrative staff feared they would soon be replaced. And they were, in part. But the economy adapted and new jobs were created alongside the new technologies that workers once feared.

That fear has returned and is alive and well today. According to some estimates, 800m jobs could be lost globally by 2030. Whilst those figures seem to be a little over-enthusiastic, it’s true that we are on the cusp of another comprehensive shake-up of the labour market.

The challenge for policy-makers and businesspeople is to find a solution to how we adapt to those changes and help ease any pain this may bring.

Successive governments in the UK have weighted our economy towards being service-led which tends to require some level of human involvement, as opposed to manufacturing which can be outsourced fully to robotics. But with the acceleration of Artificial Intelligence and machine learning, the service industries are starting to seriously assess how they can stay relevant going forward.

The reality is that there is no simple solution. Experiments with a universal basic income have come to an unsuccessful end in Finland and 77% of the Swiss public voted against such a scheme in 2016, although it remains a subject policy-makers continue to keep an eye on.

Elsewhere, governments in Asia have successfully adapted their education systems to create a generation of young people equipped with the knowledge and skill-sets to create the kinds of technologies that could one day replace humans in the workforce.

It’s high time for the UK to decide whether we embark on a serious discussion about the impact a universal basic income might have in our country, or further re-align our economy and education system with one eye on the future.

In the short-term, we have a duty to elevate the status of ‘person-led’ roles, such as carers, teachers and nurses, so that these become desirable careers that can’t be replaced by a robot or machine. The time to act is now, not later.

Whilst none of us can be sure of when this new frontier in the labour market will reach its peak, a failure to prepare could be catastrophic. We’ve all seen the Hollywood movies where robot takeovers catch unsuspecting humans off guard. They don’t tend to end well.

Kevin Craig is a businessperson, philanthropist and political campaigner. He is the CEO and founder of award-winning communications agency, PLMR.

Thanks for signing up to Minutehack alerts.

Brilliant editorials heading your way soon.

Okay, Thanks!